In 1868, Frederick Augustus Klein (1827–1903)—a German with French citizenship—started working for the British Church Missionary Society in Jordan. Late in the afternoon of August 19, during a coffee break, the sheikh of the Banî Hamîdi tribe informed Klein of a massive inscribed basalt stone (stela) lying on a nearby mound now known as Tell Dhiban. Although time was too short for a thorough inspection of the stone, Klein told Julius Henry Petermann, German consul and orientalist at Jerusalem, about the sensational discovery. Klein and Petermann’s attempt to keep the find secret was unsuccessful. News spread quickly. In addition to the Germans and French, the British became interested in acquiring the stone, and its price soared.

Before it was sold, the French sent expeditions to take impressions of the stela, known as squeezes, at times a life-threatening operation. After nerve-wracking negotiations, the Germans purchased the stela in 1869 for the sum of 120 napoleons (approximately $480 at that time, about $8,000 today). Yet they never took possession of it. In reaction to the pressure exerted by the much-hated pasha of Nablus, the Banî Hamîdi destroyed the stela by heating it and pouring cold water over it so that it broke into pieces. A rumor still circulates that the tribe thought there was gold in the stela.

Subsequently, the French archaeologist Charles Clermont-Ganneau (1846–1923) and the British General Charles Warren (1840–1927) independently collected about two-thirds of the pieces. Since Clermont-Ganneau had copies and a full impression of the original, he was able to arrange everything in the form that is now on display in the Louvre Museum in Paris. Copies of this reconstruction are in London, Berlin, and Amman (Jordan). In retribution for being cheated, the Germans published an illegal edition (Smend/Socin 1886). (In fact, an official edition has yet to be published, after nearly 150 years). Soon, money-hungry forgers produced numerous fakes, like the Medeba Stone or the Moabite pots, which in turn caused some to question—unjustifiably—the authenticity of the Mesha Stela.

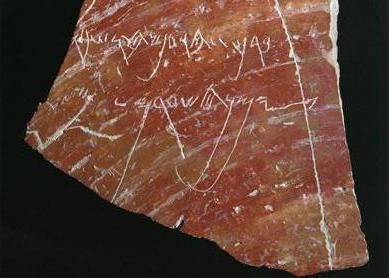

So why is the Mesha Stela important? This large stone bears an inscription (34 lines long) commissioned by the Moabite king Mesha, who is also mentioned in the Hebrew Bible (

For scholars, the Mesha Stela will continue to hold its place among the most important sources for ancient Israel for four reasons. 1) Though written from a different perspective, it is an external source confirming the historicity of several details in the biblical account of an Omride king’s reign. 2) It provides crucial data for the reconstruction of the political and religious history of Transjordan. 3) Its script is relevant to the study of ancient writing systems. 4) Its language is very similar to ancient Hebrew and thus is relevant to the study of Hebrew and neighboring Semitic languages.

Bibliography

- Na’aman, N. “Royal Inscription versus Prophetic Story: Mesha’s Rebellion according to Biblical and Moabite Historiography.” Pages 145–83 in Ahab Agonistes: The Rise and Fall of the Omri Dynasty. Edited by L. L. Grabbe. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testaments Studies 421. London: T&T Clark, 2007.

- Lemaire, A. “’House of David’ Restored in Moabite Inscription.” Biblical Archaeology Review 20, no. 3 (May/June 1994): 30–37.

- Dearman, Andrew, ed. Studies in the Mesha Inscription and Moab. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1989.