According to the Hebrew Bible, David and his house—his descendants—were appointed by God to rule all Israel (

In several places, the Hebrew Bible ties the health and fate of the kingdom of Judah to the religious conduct of its leaders, David’s descendants. Kings who tolerated the worship of foreign gods brought on disastrous consequences. The secession of the Israelite tribes after Solomon’s death is attributed to this problem (

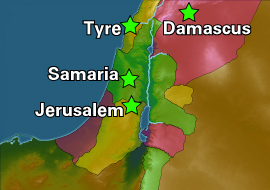

The biblical use of the term “house of David” draws attention to God’s choice of David and his descendants as an enduring dynasty, but in the wider ancient Near East, “house of David” would also have had a geopolitical meaning. It was common for a kingdom to be called the “house of” a king, with the king named being a prominent or ancestral king. For instance, the Assyrians called the kingdom of Israel the “house of Omri,” after the founder of one of its early dynasties. The ninth-century B.C.E. Tel Dan Stela, in which an Aramean king boasts of defeating the house of David, shows that the Arameans knew of the kingdom of Judah as the house of David and provides the only mention of the house of David outside of the Bible.

The tradition that the legitimate ruler of greater Israel is always a descendant of David is one of the most prominent and enduring in the Bible. Along these lines, the Hebrew Bible makes sure that it is clear that all the kings of the kingdom of Judah were, in fact, descendants of David. For instance, though at one point all the descendants of David had apparently been slaughtered, the narrative recounts that a legitimate Davidic child, Joash, was hidden by the priests and later emerged to restore the throne to the Davidic line (