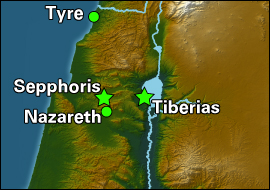

Civic and village rivalries were common in antiquity. When Nathanael asks, “Can anything good come from Nazareth?” (John 1:46), however, he voices a criticism about Jesus’ humble origins that is also expressed more widely in this Gospel. Members of the Judean elite, in particular, were unimpressed with Jesus’ allegedly rural Galilean origins (see John 7:41-42, John 7:52). Subsequent critics of Jesus’ movement may have criticized his “Nazarene” origins (see also John 18:5-7, John 19:19; Acts 6:14, Acts 24:5), since another Gospel writer, Matthew, also finds a need to justify it (Matt 2:23).

Why does the Fourth Gospel recount this question? If John wrote for an audience outside Galilee, many of his hearers might have known nothing about Nazareth except what they had heard in other stories about Jesus. Given that they would likely be unfamiliar with this negative appraisal of Nazareth, why would John bother to inform them of it? Whatever John’s audience may have known about Galilean villages, however, John can surely take for granted that even those hearing his Gospel for the first time will have heard the verses leading up to this one. If we read John 1:46 in light of what precedes it, this verse becomes rich with irony, a technique that pervades this Gospel.

For John, Jesus is not simply from Nazareth but from God (John 1:1-18, John 1:29-34). This emphasis remains clear in the immediate context. The announcement that provokes Nathanael’s protest about Nazareth is Philip’s claim that he had found the one about whom Moses and the prophets wrote (John 1:45). John’s audience may understand this claim in light of the Gospel’s announcement in John 1:17, that Jesus revealed God’s faithful love even more fully than did Moses’ law.

Philip answers Nathanael’s protest with a simple, “Come and see” (John 1:46). These words echo Jesus’ own words to prospective disciples in John 1:39. They also resemble a similar invitation offered by a Samaritan woman to her people in John 4:29. It therefore seems likely that, for John, “come and see” is a model invitation. Whether hearers are interested in Jesus (as in John 1:38-39), have heard nothing about him (as in John 4:28-29) or have legitimate objections (as here in John 1:46), the invitation is to come experience Jesus for themselves. The rest of the Fourth Gospel continues to emphasize this appeal to religious experience, initially through Jesus’ physical presence and later through the Spirit (e.g., John 16:7-15). For John, argument has its place, but it is the experience of Jesus and the Spirit that proves most persuasive.

When Nathanael meets Jesus in person, Jesus reveals something about Nathanael to him (John 1:47-48), as Jesus had done with Simon Peter the day before (John 1:41-42). Nathanael’s response is enthusiastic: “Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!” (John 1:49). Nathanael’s experience of Jesus confirms Philip’s testimony from Scripture and yields one of the many confessions about Jesus in this Gospel (see also John 1:29, John 6:69, John 11:27, John 20:28). Jesus then promises Nathanael greater revelation. He has already called Nathanael an Israelite without “deceit” (John 1:47), probably contrasting him with Jacob (Gen 27:35). Now Jesus builds on that comparison, declaring that Nathanael will witness angels ascending and descending on Jesus (John 1:51). That is, Jesus compares himself with Jacob’s ladder, a bridge between heaven and earth (Gen 28:12).

In this context, Nazareth serves an ironic function, highlighting by way of contrast Jesus’ other origin. Jesus may be from a humble hometown, but far more significantly he is king over all Israel (John 1:49, John 12:13). In John’s theology, the most significant “geographic” context for Jesus is not a Galilean village but that he is from God (John 1:29-34) and is a bridge between heaven and earth (John 1:51).