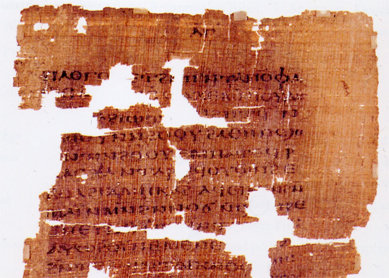

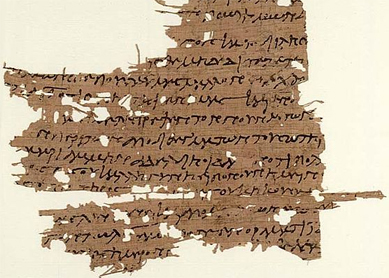

The Gospel of Thomas is unlike any other gospel text and has been an enigma ever since its discovery within the Nag Hammadi library in 1945. Lacking any narrative whatsoever, its 114 sayings are difficult to understand.

By 1977, when the 12 bound volumes comprising the Nag Hammadi library were first published in English, scholars were referring to their 52 texts as Gnostic. But what did that mean? According to the scholars who originally worked on the Gospel of Thomas, the text contained two Gnostic elements. First, it purported to contain “hidden” or “secret” knowledge (Greek, gnosis) that, if properly understood, could lead a keen reader to salvation. In the classic formulation of German scholar Hans Jonas’ The Gnostic Religion (1960), gnosis is the salvific knowledge of one’s spiritual origins. The Gospel of Thomas states early on that gnosis is its chief goal: “Whoever discovers the meaning of these sayings will not taste death” (GosThom 1). Second, Jesus behaves differently in the Gospel of Thomas than he does in the canonical gospels. He gives very strange advice, and there’s no account of his crucifixion and resurrection. Even more remarkably, the Gospel of Thomas’ Jesus seems to suggest that a reader who gains proper gnosis can actually become not a Christian but a Christ. Rather than placing their faith in Jesus, readers are encouraged to seek their inner Christ to find salvation.

Is it obvious, then, that the Gospel of Thomas is a Gnostic text? Not so fast. For one thing, scholars have recently demolished the category of Gnosticism, noting that the term was a 17th-century invention that never appeared in antiquity. The adjective “Gnostic” must not have meant anything mysterious or subversive to ancient people, because various writers (including, famously, the third-century Christian, Clement of Alexandria) used it to describe themselves. Still, many second-century Christian texts had gnosis as their goal.

But there’s another problem with characterizing the Gospel of Thomas as Gnostic. Based on its textual features, many scholars date it as early as the Gospel of Mark. The Gospel of Thomas shares many sayings with New Testament gospels, but with less elaboration and no narrative framework. For example, Jesus compares the kingdom of God to a mustard seed (GosThom 20). The synoptic gospels contain a longer version of the same saying, with each writer adding a few details about the nature of the tree and the birds that perch in it (

Recently, scholars Mark Goodacre and Simon Gathercole have argued the reverse—that the sayings of the Gospel of Thomas are an abbreviated version of earlier, canonical gospel sayings. No convincing evidence proves that short gospel sayings actually got longer over time. Perhaps the author of the Gospel of Thomas felt that it was acceptable to omit certain details—for example, about the shadow cast by the mustard tree—to get to the point of the parable. This theory pushes the date of the Gospel of Thomas much later, probably to the second century. It supports the argument that the Gospel of Thomas is Gnostic, since this was the period in which many so-called Christian Gnostic texts appear to have been written and circulated. Many of these texts share a characteristic idea: that self-knowledge is salvific. As Jesus says in the Gospel of Thomas, “The kingdom is inside of you, and it is outside of you. When you come to know yourselves, then you will become known, and you will realize that it is you who are the sons of the living father” (GosThom 3).