The central figure of the book of Daniel is very likely a fictional character, perhaps inspired by a real person from the ancient Near East known for his wisdom and good judgment (see

The dangers and difficulties that Torah-observant Jews faced during the second century B.C.E., especially during the reign of the Seleucid king Antiochus IV, led to the writing and circulation of the book of Daniel and a number of related materials soon after. In due course, some of these related materials were added to the Greek version of Daniel.

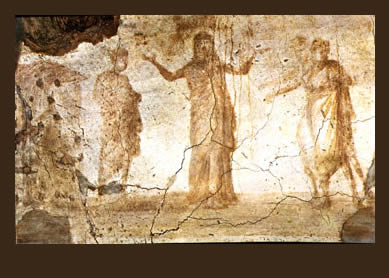

These additions include the Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Youths, Susanna, and Bel and the Snake. The Prayer of Azariah is uttered by Abednego, one of the young men in the furnace (see

The stories of Daniel were well-known by Jews in the second century B.C.E. On his deathbed Mattathias, father of Judah Maccabee and his brothers, reminds his sons of the example of Daniel and the three youths (

The popularity of Daniel and the writings associated with him is attested in the Dead Sea Scrolls, which include eight fragmentary scrolls of the book of Daniel as well as stories about the repentance, prayer, and healing of the Babylonian king Nabonidus; a dialogue between Daniel and Belshazzar; an account of Israel’s history mentioning Nebuchadnezzar and Daniel alongside a prophecy of the “end of evil”; and a prophecy foretelling the coming of one who will be called “Son of God” and “Son of the Most High.” Other scrolls mention Daniel’s prophecy of a coming anointed one (

Daniel receives a great deal of attention in the writings of the Jewish historian Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews 10.188-280; 11.337; 12.322), probably because Josephus saw in this figure an example of how to engage the pagan world successfully. Daniel was also popular in Christian literature, largely because of his visions and prophecies (see

Bibliography

- Flint, P. W. “The Daniel Tradition at Qumran.” Pages 329-67 inThe Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception, ed. by J. J. Collins and P. W. Flint. Vol.2. Leiden: Brill, 2001.

- Moore, C. A. Daniel, Esther and Jeremiah: The Additions. Vol. 44 of The Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries. Garden City: Doubleday, 1977.

- Collins, J. J. Daniel: A Commentary on the Book of Daniel. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993.