Abraham is one of the most important figures in the New Testament. Matthew traces Jesus’ genealogy back to him (Matt 1:17). Faithful Jews are called “sons” or “daughters” of Abraham (Luke 13:16, Luke 19:9) and are given the promise that he will be there to meet them when they depart this life (Luke 16:22). A summary of his accomplishments occurs in Acts 7 and Heb 11, and two incidents stand out. First, he was willing to leave his own country and trust God to lead him to a new one. Second, be believed God could make him the father of many nations, even though his wife Sarah could not have children. Indeed, James thinks his faith was so great that he would have offered his son Isaac as a sacrifice if that was what God wanted (Jas 2:21). Fortunately, it wasn’t (see Gen 22).

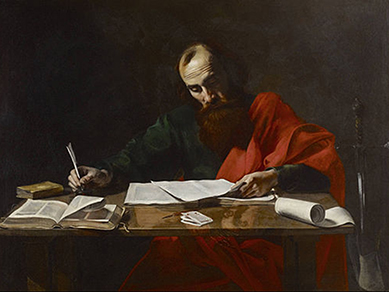

Abraham’s faith was also important to Paul, but he uses it to make a different point. Some Jewish Christians insisted that Gentile Christians needed to be circumcised to belong to the people of God (Acts 15:1). After all, Gen 17:12-13 calls circumcision an “everlasting” sign of the covenant, and says that it applies to any foreigners living in their midst. How can these Gentile Christians claim to have faith in God if they are unwilling to do what God requires?

Paul sees it differently. He thinks the demand for circumcision contradicts the gospel, where there is “no longer Jew or Greek … slave or free … male and female” (Gal 3:28). But he does not wish a separation between the children of Abraham and his Gentile converts, who can rightly be called children of Abraham because they share the faith of Abraham (Gal 3:6-9). Indeed, Paul can argue that Christian faith is similar to Abraham’s faith because both involve believing that God “calls into existence the things that do not exist” (Rom 4:17). Hebrews contains a similar argument, where Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac is similar to faith in resurrection, for he “considered the fact that God is able even to raise someone from the dead—and figuratively speaking, he did receive him back” (Heb 11:19).

If Paul is correct that Gentiles can be included in the people of God without needing to be circumcised, then God appears to contradict God’s own prior commands. Can such a God be trusted? This is the topic of Rom 9-11, where Paul notes that Ishmael was also a son of Abraham but was excluded from Israel. He deduces from this that it is not biological descent that defines God’s people but responding to God in faith, precisely what his Gentile converts have done. In his letter to the Galatians, he is particularly daring. He uses the two sons as an allegory of two types of people: those who are free and those who are slaves. Since he thinks the demand for circumcision is a form of enslavement, he suggests that his opponents show themselves to be children of the slave woman rather than children of the promise (Gal 4:22-31).

Bibliography

- Dunn, James D. G. Jesus, Paul, and the Gospels. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2011.

- Moyise, Steve. The Later New Testament Writers and Scripture. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker; London: SPCK, 2012.

- Moyise, Steve. Paul and Scripture. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker; London: SPCK, 2010.