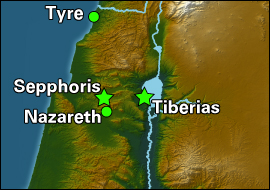

Herod Antipas, son of Herod the Great, ruled from 4 BCE to 39 CE over the Jewish provinces of Galilee and Parea. His official title was “tetrarch” (meaning “ruler of a fourth” of his father’s kingdom). By most standards, he was just an ordinary, local, Jewish ruler, but two incidents during his reign secured him a high place in the history books. First, he killed John the Baptist. This incident is recorded by the Jewish historian, Josephus, as well as by the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke). Next, he met with Jesus, whom Pilate sent to him. This encounter is recorded only by the Gospel of Luke.

Why did Herod Antipas execute John the Baptist?

When Herod the Great died, the question of succession became a matter of great dispute. Several of Herod the Great’s sons courted Emperor Augustus in Rome wishing to inherit their father’s kingdom. At the same time, some Jews sent a delegation to get rid of Herodian hegemony altogether. Antipas entered the race with the intention of becoming his father’s sole heir with the title of king (cf. Josephus, War 2.20); yet he was only assigned the second-best part of the kingdom, Galilee and Perea, and only with the inferior title of tetrarch.

Throughout his life, Antipas tried to rectify his bad start by making a good impression in Rome and thereby rise in the ranks. To earn the trust of his patron, the new Emperor Tiberius, Antipas had to keep his area calm. Only in this way could trade prosper and Antipas be able to assist the Roman army in various expeditions in the eastern region of the empire, as a client ruler was expected to do.

This desire helps explain Antipas’s reaction to John the Baptist, who at first sight would seem to be an insignificant, laughable hillbilly. However, in the eyes of many Jews at the time, John was a prophet from God. Josephus relates that a significant following of Jews, greatly affected by John, seemed willing to carry out all of John’s instructions. Antipas feared that John’s movement would lead to rebellion, so Antipas preemptively imprisoned John at Machaerus (Antipas’s castle east of the Dead Sea) and later put him to death as a rebel.

The Synoptic Gospels likewise describe John as a popular prophet gathering huge crowds, but according to Mark and Matthew, John’s execution was instead a response to his religious critique of Antipas’s impious marriage to his brother’s former wife, Herodias. In these accounts, Antipas feared John, because he viewed him as “a righteous and holy man.” Antipas even “liked to listen” to John, though he was “greatly puzzled” by him (Mark 6:20). Therefore, Herodias used her daughter’s dancing ability to charm Antipas and thereby trick Antipas into killing John. Herodias’s plot proved successful: John was executed and his head delivered to Herodias’s daughter on a platter (Mark 6:27-28).

Why did Herod Antipas wish to execute Jesus?

According to the Synoptic Gospels, Herod Antipas was also a “shadow of death” over Jesus. In these accounts, Antipas and the “Herodians” (possibly Herodian officials or adherents) saw Jesus as a threat to be eliminated (see Mark 3:6; Luke 13:31; Matt 14:2). However, it is not stated exactly why Jesus was a threat. As a matter of fact, the Gospel of Luke builds up tension between Antipas and Jesus marked by equal fascination and rejection (see Luke 9:9 vs. Luke 13:31-32). When they finally meet in Jerusalem during the trial of Jesus, an almost absurd scene evolves. First Antipas is said to be “exceedingly glad” to see Jesus, since for a long time he had hoped to see him perform a miracle. But when Jesus remains silent, the excitement turns to contempt and mockery. Antipas finally dresses him in a bright, shining robe and sends him back to Pilate, the Roman governor, who sent Jesus to Antipas in the first place when Pilate learned that Jesus was from Galilee. Perhaps not surprisingly, scholars disagree on how to interpret Luke’s view of Antipas’s role in the execution of Jesus. Was his mockery and dressing of Jesus a sign of condemnation or acquittal? While Luke himself states the latter (see Luke 23:14-15), Antipas is nonetheless later remembered as one among those responsible for the execution of Jesus (see Acts 4:27).

Stepping back from these two particular incidents that earned Herod Antipas a place in our history books, the sources on the life and reign of Antipas remember a local ruler, who managed to stay in office for a very long time (some forty-three years), but who never was able to fulfil his lifelong dream of becoming king. He ended his days in France, of all places, to where he was banished by Emperor Gaius Caligula, because he had dared to ask for the title of king (Josephus, Antiquities 18.240-255).

Bibliography

- Jensen, M. H. “Herod Antipas: New Testament.” The Encyclopedia of the Bible and Its Reception . Berlin: de Gruyter, 2015.

- Darr, J. A. Herod the Fox: Audience Criticism and Lukan Characterization. JSNTSup 163. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998.

- Jensen, M. H. Herod Antipas in Galilee: The Literary and Archaeological Sources on the Reign of Herod Antipas and Its Socio-economic Impact on Galilee. WUNT 2/ 215. 2nd ed. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010.