In the Hebrew Bible, “sin” is more than a religious label and “guilt” is more than a feeling. They are central elements of the human condition that may plague the individual and the nation, pollute the sanctuary and the land, and prevent safe human-divine interaction. Sin and guilt produce a real burden on a person and perhaps even a community, one that persists until dealt with appropriately.

In general, sin is an error understood to be serious enough to produce a real stain or burden that weighs on an individual. Sin can be intentional or unintentional, and it can be an act (such as murder) or a failure to act (such as not testifying as a witness to a crime). Where sin is the cause, guilt is the effect—the logical consequence of having committed a sin. Guilt may lead to death if unaddressed.

The consequences of sin could manifest in several ways. In court, for example, a person convicted of a crime was guilty and had to pay the assigned penalty. People might also feel guilty, which is not the problem in itself but rather an indication that they know that they have committed an offense. Suffering could also trigger the recognition of guilt. In the world of the Hebrew Bible and the ancient Near East, people generally believed that the cycle of sin, guilt, and punishment functioned like a natural law, much like we think of gravity. Committing a sin led naturally to negative consequences for the sinner. So, if people encountered hardship, the conclusion was that they must be guilty of some sin. However, the book of Job in particular wrestles with the possibility that the law of sin, guilt, and punishment is not absolute and that certain righteous people may suffer and wicked people may prosper.

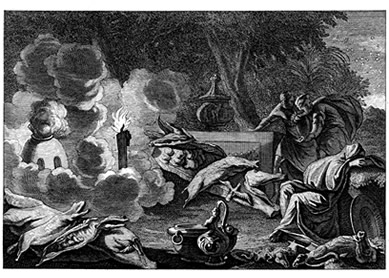

Although sin generally led to punishment, punishment could sometimes be avoided through prayer, vows, offerings, or ritual activity intended to convince God to remove the burden and its consequences. The Priestly texts, which describe the sacrificial system associated with the tabernacle, outline various sins and the rituals required to cancel their effects. In

Nonetheless, there is no way to remove the effects of the most serious sins—such as murder or idolatry. Such sinners may appeal to God through other means, but if this too fails, they must suffer the withering consequences of their sins, including agricultural and economic hardship, sickness, shame, and death.

Sin had especially serious and volatile effects when it and those who bore its weight came into contact with the divine sanctuary. Since divine holiness was incompatible with human sin, sinners could not safely access divine space unless their sin was removed from them (see, for example,