Rome’s power involved not only military supremacy and political control but also economic reach, manifested in its exploitation of its land, production, and people. Rev 18 illustrates how integral economic activity was to the empire. This chapter celebrates Rome’s downfall by focusing on its economic power, condemning the luxurious wealth shared by client kings and some merchants (Rev 18:3, Rev 18:9).

The book of Revelation sees participation in imperial economic practices as incompatible with being a Jesus-believer (Rev 13:16-17, Rev 18:4-5). The author pictures people with a mark indicating that they either participate in the imperial economy or belong to God (Rev 7:3). One cannot have allegiance to both. These allegiances collided in civic festivals and in craft and artisan guilds, where members made offerings or prayed to imperial images at regular meetings. Participation in these arenas seems to have been problematic at least for the writer of Revelation, who saw the empire as a tool of the devil to promote idolatrous worship of the emperor (Rev 13), for which it was under God’s judgment (Rev 18). The writer’s condemnation of Jesus-believers who eat food offered to idols and who participate in Roman culture (denoted by the metaphor “fornication”) in Rev 2:12-19 indicates, though, that some (perhaps most) Jesus-believers saw participation in imperial society as necessary and legitimate.

The Roman Empire was socially and economically hierarchical. Great power, wealth, and status resided in the hands of a very small ruling elite. As the parables of Jesus indicate (compare Mark 12:1-12; Matt 20:1-16), land provided the basis of wealth. The empire had a proprietary economy, with the emperor asserting control over land (and sea) by claiming a share of all produce (such as crops and livestock) through taxes and tributes. It was thus also a tributary economy, in that these taxes and tributes were paid in goods rather than cash. Historians debate the precise levels of taxation, but for small farmers trying to sustain extended families and pay multiple levels of taxes and rents to imperial, regional, and local powers, the impact could be severe.

Although elites conspicuously consumed and displayed wealth, most folks lived much less opulent lives. Some experienced a level of comfort and security, but most, especially those with few or no skills and only their labor to sell, lived precariously around and below subsistence levels, as described in Matt 25:31-46. This text not only attests extensive poverty but also declares God’s judgment on the imperial system for creating, and failing to provide for, the pervasive poor. The physical and psychological damage of the imperial system is reflected in the numerous sick and demon-possessed people who populate the Gospels. Jesus’s healings and provisions of abundant food not only repair some imperial damage but also anticipate God’s world, in which all have access to adequate resources, nutrition, and physical well-being. In the meantime, almsgiving, shared resources, loans, and benevolent patrons provided survival strategies (Matt 5:42, Matt 6:2-4). The book of James also mentions the economic exploitation and social disdain for the poor that sustained massive economic disparities (Jas 1:9-11, Jas 2:1-26, Jas 5:1-6).

Both the luxurious existence of the ruling elite and the proprietary nature of the empire are evident in a list in Rev 18:11-13 of some 28 items that merchants carried from the provinces to Rome and its elites. The list is by no means complete, but we can notice the types of luxurious goods that elites enjoyed: precious metals and stones, fine textiles, exotic woods and ivory for furnishings, plant products, food and wine products, and animals and their products.

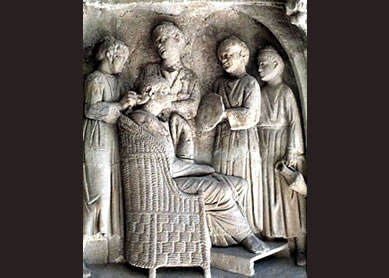

The list ends by referencing “slaves—and human lives.” The Roman economy was a slave-based economy. Slaves could be war captives, those born into slavery, abandoned children, those seized and sold by brigands, and, notably, adults enslaved as a result of debt. Slave conditions varied enormously depending on several factors, including the master, their skills, gender, attractiveness, and the physical strength of the slave. There is evidence for brutal treatment of slaves (including unlimited sexual access) as well as genuine care. There is little evidence that anyone thought about abolishing slavery or that any such efforts existed.

The Roman economy, based on land and trade, favored elites and sustained an extravagant lifestyle marked by conspicuous consumption. Most of the population, however, was to varying degrees poor. Their daily life was precarious, with a constant struggle to supply necessities.

Bibliography

- Horsley, Richard. Covenant Economics: A Biblical Vision of Justice for All. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2009.

- Longenecker, Bruce W. Remember the Poor: Paul, Poverty, and the Greco-Roman World. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2010.

- Carter, Warren. The Roman Empire and the New Testament: An Essential Guide. Nashville: Abingdon, 2006

- Morley, Neville. The Roman Empire: Roots of Imperialism. London: Pluto Press, 2010. Pages 70-101.

- Garnsey, Peter, and Richard Saller, The Roman Economy: Economy, Society, Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987. Pages 43-103.

- Howard-Brook, Wes, and Anthony Gwyther. Unveiling Empire: Reading Revelation Then and Now. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis, 1999.