Q. Does James Jacques Joseph Tissot’s painting The Flight of the Prisoners depict the period between 586 and 539 B.C.E., when the leaders and elite of Judea were exiled to Babylon? If so, is this referred to as the Babylonian exile? And are the men shown with bows (to the left of the refugees) supposed to be Babylonian soldiers overseeing the exile?

A. This question raises important issues of biblical interpretation and the way that different generations receive and rearticulate the biblical materials. Increasingly, biblical scholars study visual representations of the text to establish a wider field of meaning for the Bible.

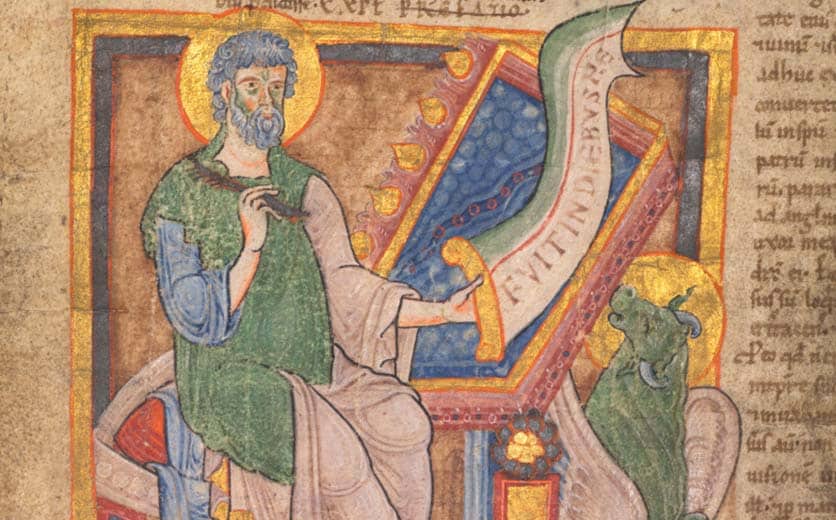

Details in Tissot’s painting appear to coincide with Jerusalem’s destruction at the hands of the Babylonians as described in

James Jacques Joseph Tissot painted The Flight of the Prisoners during the last years of his life, not long before his death in 1902. By that time, according to Tissot’s biographer Michael Wentworth, the painter had made three trips to Palestine (between 1885 and 1896) to research the more than 500 biblical paintings he made in the last two decades of his life.

Although certain of the painting’s details are consistent with the biblical narrative set in 586, others are not—for example, not all the walls of Jerusalem are leveled (as in

In Wentworth’s view, Tissot gathered a great quantity of material but was not very discriminating in the process. Some of the sources were even faulty, and as a result the research lacked historical or archaeological accuracy. Wentworth concludes, “With this pseudo-scientific file of visual materials, Tissot set about his illustrations. If the ‘facts’ of his fin de siècle Jerusalem are superficial and personal, they still smack of the naturalists’ approach in their insistence on realistic detail.”

A case in point is the armed guards in The Flight of the Prisoners. They are finely detailed—based, in all likelihood, on rustics that Tissot encountered in Palestine. (He chose a young Yemenite as his model for Joseph the father of Jesus.) Although the realistic appearance of the guards does not reflect the historical Nebuzaradan and his forces, the connection to the biblical story is clear in Tissot’s depiction of Jerusalem’s fall in the sixth century b.c.e.